At Emma, we decided to rebuild our entire technology landscape from scratch back in 2021. We launched an organization-wide re-platforming initiative to migrate from our Magento monolith to a composable commerce architecture based on the MACH principles. A decision that has been described in detail in a series on the topic.

Throughout the re-platforming, we had to prioritize ruthlessly to meet our ambitious timelines and we faced multiple tough decisions regarding what to build now and what could wait. A prime example being our promotion engine.

The need for a new promotion engine

We are using commercetools to enable our e-commerce, and it comes with a built-in promotion engine that is both powerful and flexible. Despite its capabilities, however, we knew from the outset we would eventually reach its limits due to the scale and the nature of how we do promotions at Emma.

Our forecasts indicated we could leverage commercetools’ promotion engine for 1-2 years, so we decided to take on prudent and deliberate technical debt by deferring the decision to build or integrate a different promotion engine, thus allowing us to allocate capacity to more urgent topics with immediate impact.

Inevitably, the day came when we hit the limits and needed a new promotion engine. The most important pain points we had to address were:

Limited search functionality. Our marketers struggled to effectively manage the campaigns due to limited search functionality that severely impacted the discoverability and governance of the campaigns.

Weak market isolation. Promotions were global, meaning they could not be scoped to specific markets. This was poorly aligned with Emma’s decentralized marketing organization, and led to high business risk as markets could easily interfere with each other.

Inefficient evaluations. Due to global promotions, all promotions rules were evaluated for each cart. For an organization where the vast majority of promotions are market-specific, this implies a lot of unnecessary evaluations.

No support for dynamic bundles. Dynamics bundles are heavily used by our marketing teams, and there was no native support for them, leading to complicated and error-prone workarounds.

Hitting scalability limits. We were rapidly approaching hard limits on the number of campaigns we could run.

No way to enforce compliance. The promotion engine was so flexible that it became error-prone and risky, as there was no way to create constraints to ensure compliance.

Complicated coupon management. Managing coupon campaigns was complex and hard to debug, as coupon codes and campaigns were separate entities. Moreover, bulk generation of coupon codes could not be offered as self-service and instead, the marketeers had to rely on engineers.

After evaluating our options and researching available solutions, we concluded that Talon.One was the best candidate to address the above paint points.

Armed with context and a solution, we bootstrapped a small integration team of senior engineers and got to work.

The starting point: Tightly coupled entities

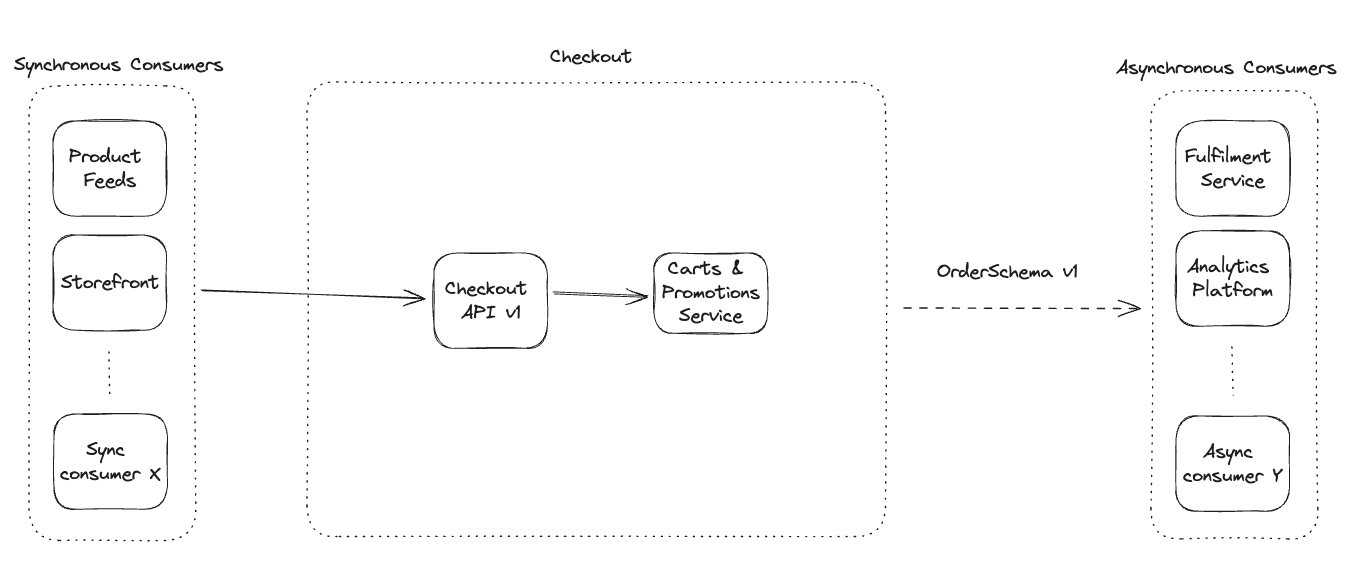

To understand our journey, we need to first understand where we started. The overall architecture, dependencies, and imperfections that surrounded our promotion logic. A high-level architecture is depicted in the image below.

Figure 1. The high-level architecture before the migration.

There are synchronous consumers, like our storefront, that interact with carts and promotions using a Checkout REST API. Additionally, there are various asynchronous consumers downstream, for example, services responsible for fulfilling the orders and our analytics platform.

In this architecture carts and promotions were tightly coupled in the backend, and this coupling was leaked to synchronous consumers through the Checkout API and to the asynchronous consumers through our OrderCreated schema. Consequently, all consumers were tightly coupled to the backend-specific handling of promotions. A dependency that effectively made it impossible to integrate a new promotion engine without introducing breaking changes for all consumers.

Another limitation in our workflow was stale prices and promotions. They were never updated after a product had been added to the cart. A recalculation of prices happened right before the customer was about to pay, making it a surprise to the customer and thus a poor experience.

Finally, the representation of promotions was not consistent for upstream and downstream consumers, leading to business logic being duplicated in multiple places.

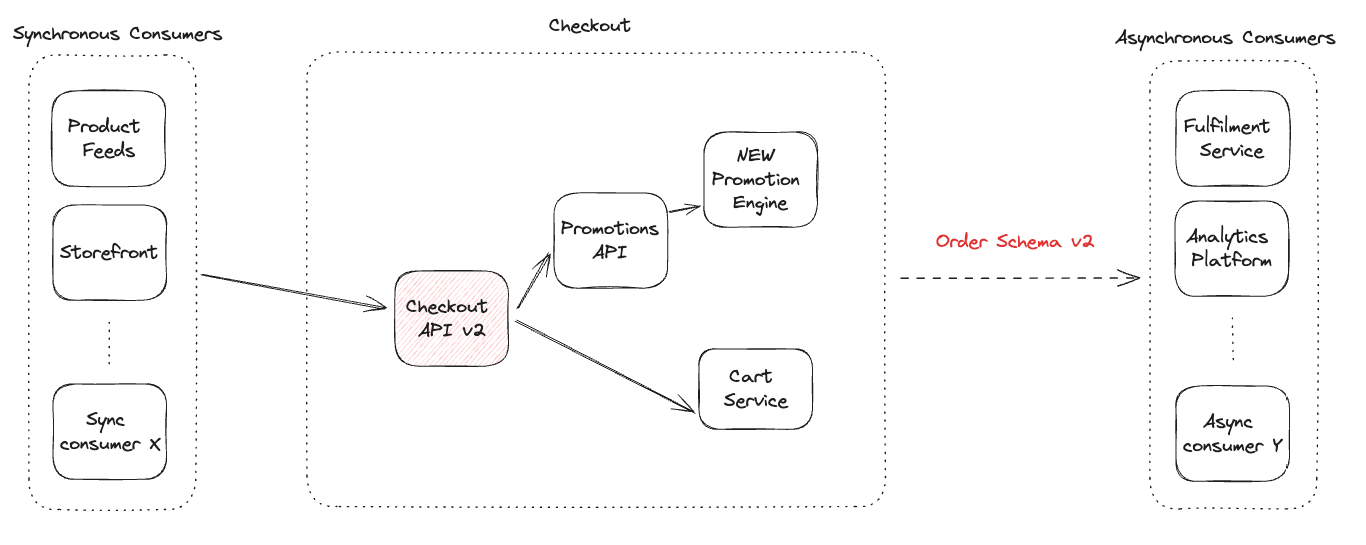

The target state: Anything-as-a-promotion-engine

The diagram below shows our target state with the breaking changes highlighted in red. The architecture below loosens the coupling by exposing consistent promotion-agnostic interfaces for both synchronous and asynchronous consumers, and by decoupling carts and promotions in the backend. This architecture not only allowed us to replace our existing promotion engine with Talon.One, but also makes it easier to integrate a different promotion engine in the future, i.e., anything-as-a-promotion-engine.

Figure 2. The high-level architecture after the migration.

Comparing the target state to our initial architecture, we can spot three new kids on the block: a) Checkout API v2, b) Promotions API, and c) Order Schema v2. These building blocks are described below.

The building blocks

Promotions API

The first piece of the puzzle was the Promotions API. An API that would act as a middleware between the cart functionality in the backend and any promotion engine. This abstraction layer allows multiple promotion engines to run in parallel and simplifies integrating other promotion engines in the future.

Some might rightfully say that we are treading into YAGNI territory with the above arguments. However, the most important aspect of the Promotions API was immediate risk management. Being able to run our legacy promotion engine alongside Talon.One meant we could apply the strangler pattern to rolling out markets, i.e., doing one market at a time.

Modelling the interface

The schema for the new promotion entity was modeled as having two discount types, discount and discount code. Those types could be associated with two entities, the cart or specific line items. The high-level schema of the new promotions was defined as:

- provider - string. The name of the promotion engine, either "Commercetools" or "TalonOne".

- discountCodes - an array of DiscountCode objects. These represent discount codes on cart level.

- discounts - an array of Discount objects. These represent discounts on cart level.

- lineItemPromotions - a map of LineItemPromotion. These represent promotions applied to specific line items.

- nonApplicableDiscountCodes - an array of DiscountCodes. The purpose of these are described later.

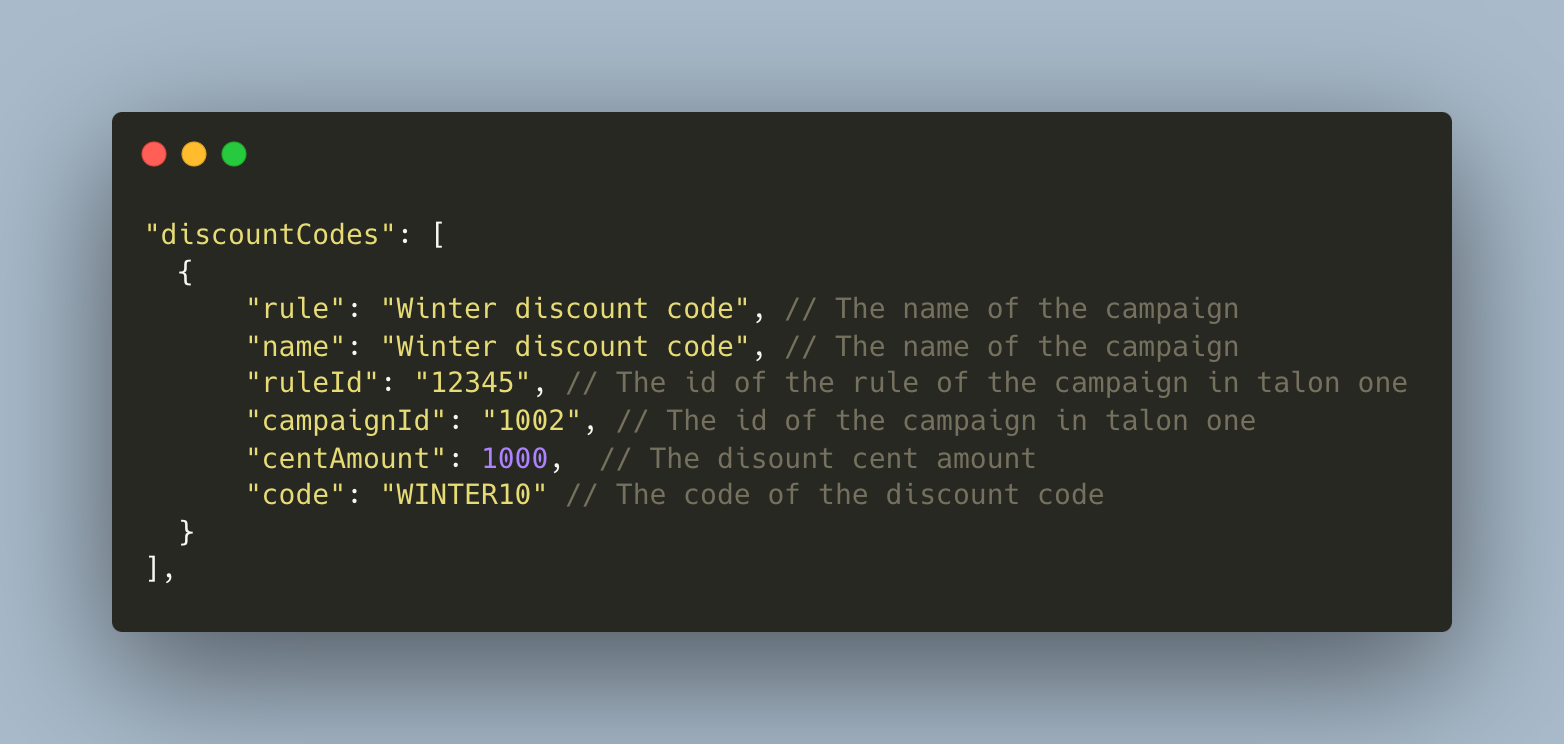

The detailed schemas of the objects are not relevant for this article, but to give an idea, a discount code looks like:

Figure 3. An example of a discount code representation.

The other type, discount, is identical to discount codes with the difference that it is missing the field code.

Deciding on service granularity

One architectural decision we faced during the design of the Promotion API was whether to create it as an independent service or as a module in the existing Checkout API. A simplified tradeoff analysis is summarized in the table below.

| Reasons to keep as one service | Reasons to create a separate service |

| They share code since both interface with our e-commerce backbone, commercetools. | Promotions are business-critical to Emma and will be managed by a dedicated team in the future. |

| They are part of the same workflow, thus communicate extensively. | To be able to deploy independently, without being coupled to the release cycles of the Checkout API. |

We ended up decided for a separate service as we identified the need to deploy independently to be the most critical factor in this project, as we optimized for minimizing time-to-market.

Checkout API v2

The next building block was the synchronous API. We had to re-design the Checkout API to foster a looser coupling. The initial version was tightly connected to the native commercetools schema, meaning we could not swap commercetools as a promotion engine without the storefront breaking.

We wanted to create an API that maintained consistency irrespective of the promotion engine being used. The objective was to forge an interface that could facilitate the synchronous consumers’ migration to the new API concurrently with the integration of the new promotion engine into the backend. This parallel migration was crucial, given they were carried out by separate teams.

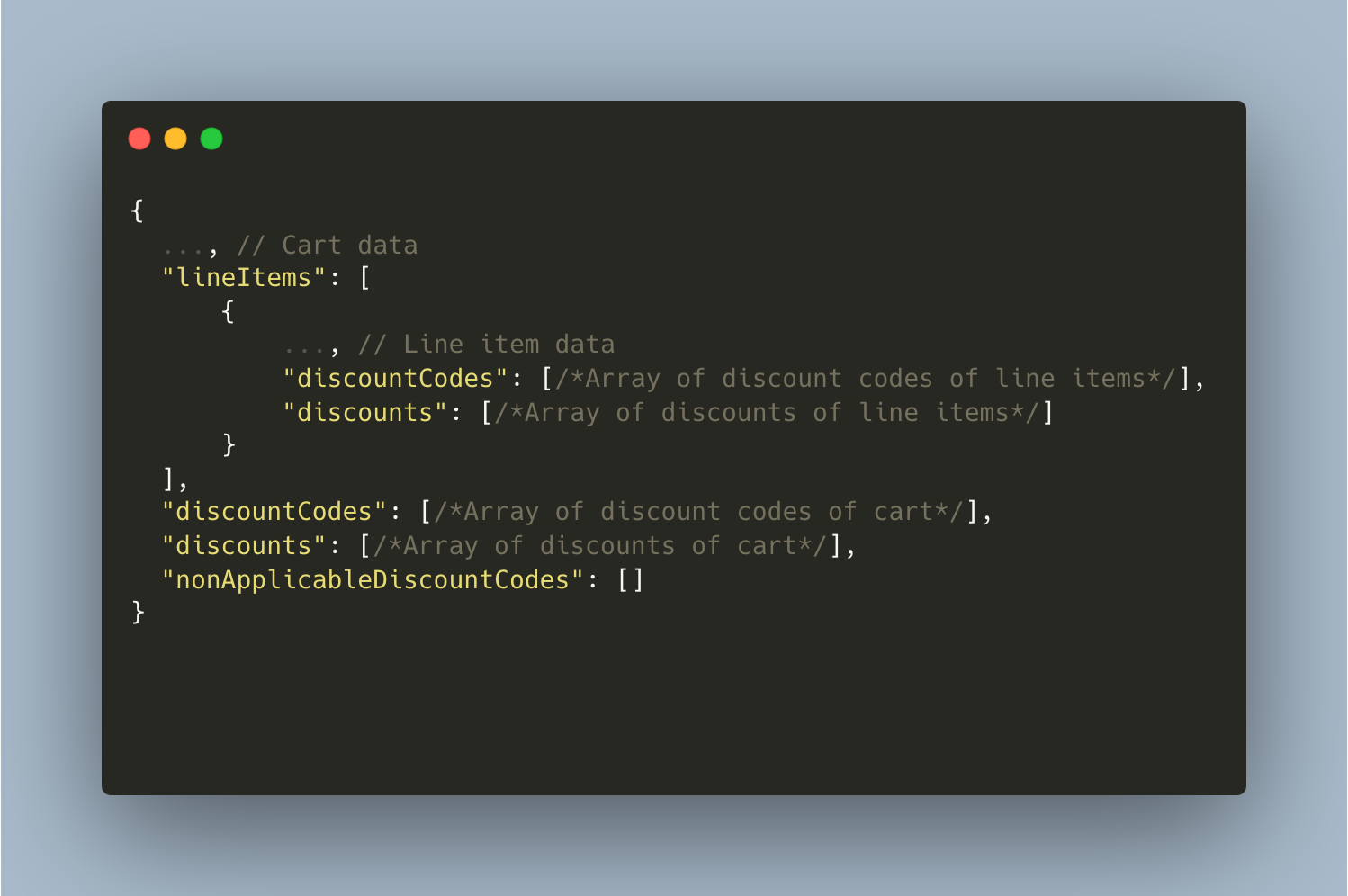

We leveraged the new promotion object described above to associate carts and line items with discounts and discount codes. The representation of a cart in Checkout API v2 is depicted below:

Figure 4. An simplified representation of the cart in Checkout API v2.

As seen in the schema, there is a key called nonApplicableDiscountCodes. It is a list of valid codes (meaning they should not be rejected) that yield a zero-value effect. This could mean, e.g., applying a discount code that requires a minimum cart value before the minimum cart value has been reached. Allowing this behavior was necessary to cater to the requirement that a user should be able to successfully add coupons to an empty cart, e.g., when clicking on a UTM link.

Improving the customer feedback

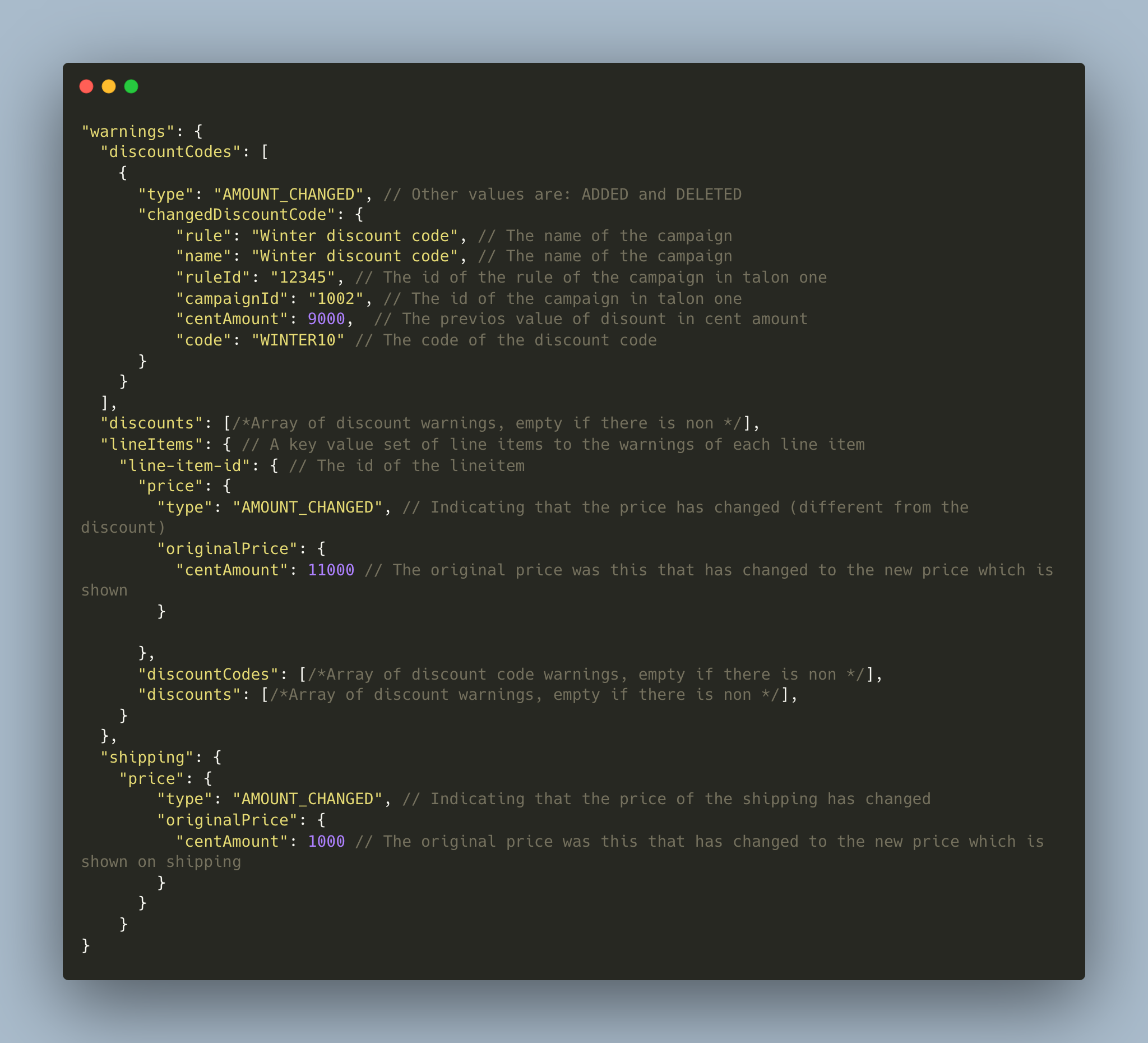

Additionally, we extended the Checkout API with a warnings object. This addressed our previous limitation that we never provided feedback to the customer if there was a price or discount change. The warning object provides information to the client about any price or discount related change that was not caused by any customer action.

The warnings can stem from price updates on products and shipping, discounts, and discount codes, and they can be associated with both the cart and specific line items. An example of the warnings object can be seen below.

Figure 5. An example of the warnings object.

Now, the final piece of the puzzle was to make the async API, the OrderCreated event schema, consistent with the new promotion object.

Order Schema v2

Like the synchronous API, we also depended on native commercetools fields in our asynchronous interface, i.e., the OrderCreated event schema. We deprecated those fields and extended the schema with the promotion object described above. The updated schema enabled the downstream teams to migrate while the integration team was integrating the new promotion engine.

With the building blocks defined, i.e., the how, we also had to decide on sequencing, the when.

First expand, then migrate, and finally contract

We optimized for short time-to-market. However, we also had to carefully manage risk, given the business-criticality of the checkout. We generally move fast, break things, and fix them later, although when dealing with discounts, prices, and the overall checkout, we had to tread more carefully.

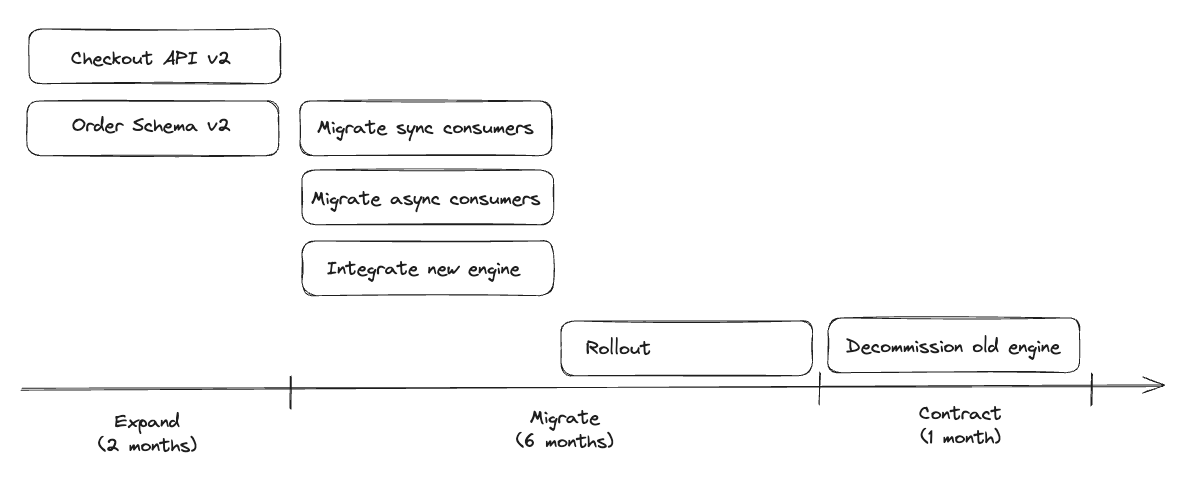

Therefore, we chose to carry out the migration using the parallel change pattern, i.e., in three phases: expand, migrate, and contract. In the first phase, the expansion, we designed and implemented the v2 interfaces for our consumers. Running v1 and v2 in parallel laid the foundation for the migration phase, as all consumers could migrate while the integration team worked on building out the Promotions API and integrating Talon.One.

When the consumers were running on the new versions and Talon.One was integrated, the rollout of markets could begin. We started with small markets, and doing them one by one, before incrementally adding complexity and doing markets in bulk. Finally, we deleted old endpoints, removed access to the old promotion engine, cleaned up some configuration, and decommissioned the old promotion engine.

A high-level roadmap can be seen in the picture below.

Figure 6. The migration roadmap.

Go slow, to go fast

9 months after we set out on the journey described in this post, we migrated our 22nd and ultimate market to Talon.One, and we dismantled the integration team. We are deeply grateful to everyone who made this happen.

This was a significant undertaking that involved around 30 teams and close to 400 users. We managed to replace a key component of our checkout with zero downtime. A testament to the flexibility of composable commerce, and a strong product and engineering organization.

The approach to first re-designing the interfaces to foster loose coupling required significant upfront investment, however, it was key to enable a swift rollout while mitigating risk. We went slow, to go fast.

Comments